June: Scoliosis awareness month |

| Images of yoga poses and personal anecdotes about yoga retreats and the latest trends in yoga are all-pervasive. Stunning images featuring, (usually) young, white women in athletic and often gymnast-style poses, in tropical or visually arresting locations take up a lot of space in the world of social media. No doubt, these are aesthetically pleasing but they really aren’t doing the practice of yoga justice, and may be off-putting to many who would benefit from this ancient and life-changing practice, which, if you didn’t know, is so much more than postures. |

Let’s be clear from the outset, yoga is for everybody.

All are welcome here.

Starting where you are now is the right place to start. You do not need to look a certain way, shape, size, colour, or sex. As you are now is perfect. You are ready to begin, the fact you are reading this probably means your journey has already begun. How long it will take, well…read on.

Yoga is more than the postures. Yoga comes from the Sanskrit word ‘yuj’, which means ‘to yoke’. (Yoking was a practice used to connect and harness two animals. They would be ‘yoked’ together, typically at their necks, to then be able to perform tasks, such as ploughing a field.) To yoke is to create a union, and this is typically how we hear yoga defined today, a union of ‘the self’ with the ‘true-self’. Ultimately, it’s a piercing of illusion or peeling back of layers, the word ‘yoga’ in and of itself is already a paradox. The true essence of yoga is uniting two things that were never actually separate to begin with. It is just the illusion of separation that we need to remove.

What can you expect? |

Through asana we build strength in the body, promote health and remove tension and energetic blocks. We use the breath here to ensure we aren’t straining and our mind focuses on our breath, balance and openness. This is a type of moving meditation – if your mind wanders, you’ll lose the thread of your breath, or your balance, or go too deep, or not deeply enough, into the pose. Pranayama, along with other benefits, gives our mind a single focus, which again, is a kind of meditation. A specific meditation part of the class may also be offered, which also trains the mind.

The Four Ps

Alongside physical and physiological benefits these techniques also help us psychologically as (when practiced correctly) they share the quality of stilling the mind – bringing peace.

Yoga Chitta Vritti Nirodha

~Patanjali, Yoga Sutras.

Yoga is the settling of the mind into silence.

When the mind has settled, we are established in our essential nature, which is unbounded Consciousness.

Our essential nature is usually overshadowed by the activity of the mind.

When the mind has settled, we are established in our essential nature, which is unbounded Consciousness.

Our essential nature is usually overshadowed by the activity of the mind.

| As a society this is something we don’t do very often. Our minds are racing, planning, calculating, interpreting, reliving, etc., there’s a lot of internal, as well as external, ‘noise’ – there’s always something vying for our attention. We’ve gotten so used to this we frequently don’t even perceive the issue just the symptoms such as, stress, exhaustion, distraction, anxiety, etc.. |

It’s good and it keeps unfolding for your benefit.

For many beginners the novel experience of this balance, internal stillness or unity – even if only briefly glimpsed on the mat – is what captivates them. Interpreted as a sense of well-being it feels familiar and is often described as ‘home’. Most would say that this is what initially brings them ‘back to the mat’.

For many beginners the novel experience of this balance, internal stillness or unity – even if only briefly glimpsed on the mat – is what captivates them. Interpreted as a sense of well-being it feels familiar and is often described as ‘home’. Most would say that this is what initially brings them ‘back to the mat’.

| As you’ve no doubt gathered, yoga goes beyond what happens on the yoga mat or meditation cushion. We start to have those feelings in our everyday life. All areas of life are enhanced, which we could top-line describe as improvements in our relationship with others and ourselves. The benefits keep unfolding and things which do not serve us easily drop away. This is what keeps us going long-term. The steadiness and clarity we experience in practice becomes more discernible in our everyday. As we aren’t monks or renunciates it’s not of much use if the only time we can contact these qualities is when on the yoga mat or meditation cushion. We cultivate these qualities to navigate the world we live in more easily. |

We should remember:

The very root of all the yogic practices is to reach only one goal: enlightenment (freedom).

The elements within our practice are our tools for this goal.* (Don’t worry, there’s joy along the way.) If we reach a constant state of stillness and steadiness of mind we can dispense with the tools, for we’ve reached freedom, enlightenment, achieved stability in pure awareness, which is understood by some as Samadhi.

| Until Samadhi, we make like Goldilocks, getting things, “Just right!”, creating the conditions that support a state of homeostasis and that’s why it’s called a practice. Even after decades of personal practice and many years of teaching I still practice. The ‘going-in’ or ‘peeling’ is an on-going thing. The nature of our bodies, mental state and personal circumstances and other external elements is changeable. This is the human experience. What was accessible last month, year, yesterday or this morning may not be now, in this very moment, or perhaps we can go further than before because more is available to us. |

This changeability keeps the practice fresh and constantly invites us to the present moment. (Which serves us well, as the ‘now’ is the only reality. The future is your imagination and the past is impossible to live in. All you’ve got is ‘now’.)

There are many styles of yoga and I would encourage you to do your research, be open, and give it a try, see which style and teacher you gel with. A good teacher will always be able to give modifications and extensions for poses and be open to your questions. Use your brain, maybe don’t hit an Ashtanga level 2 or hot yoga class if you’ve mainly been ‘yoked’ with your couch during lockdown. There’s no shame in being a beginner, in fact, I still love taking a beginners classes as much as I enjoy teaching them (that’s my jam), it’s an inward journey after all. Find a teacher that supports you in your practice and your ‘going-in’.

*Further elements are used as we broaden our practice. Please see the yoga sutra of Patanjali for more information on the ashtanga (eight-limbs), which guide us on how to live a meaningful and purposeful life.

| As we entered lockdown last year I shared on my social channels a selection of techniques that I grouped into a practical toolkit. As we start to ease out of lockdown I thought it would be useful to give them a bit of a polish and share them again here, as they’re relevant to any period of stress and uncertainty, not just Covid-19. Life has been changed beyond our imagining back in January 2020. It’s been a long haul and more freedom is certainly welcome. For some, it comes with a degree of trepidation, this transition period is going to be both exciting and challenging. Hopefully you will draw on these resources for support. |

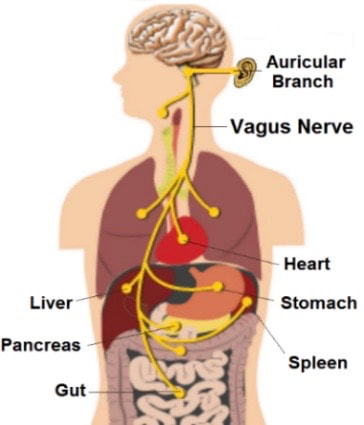

The tips I share below are aimed at getting us out of the fight-flight-freeze response (stress cycle), which many of us are in a lot of the time, and returning to rest-and-digest (relaxation) by accessing the parasympathetic nervous system. We will do this through stimulation of the vagus nerve (stay with me…).

The vagus nerve branches out from the brain stem to the inner ear, throat, diaphragm, lungs, heart and abdominal organs. Although we cannot consciously control our heart, kidneys or small intestine, we can control the muscles of respiration (breathing) and the muscles of the larynx (that open and close the vocal cords and control the pitch of sound). To facilitate the parasympathetic response in the body (and stimulate the vagus nerve), we need to exert influence over those two main areas, namely breath and sound.

Firstly, WORKING WITH BREATH

| Deep diaphragmatic breathing is where it’s at. You’re no doubt familiar with the image of someone experiencing panic and scenes of them hyper-ventilating, it’s noisy, distressing and very obvious. Oftentimes, we’re actually doing a less outwardly dramatic version of this. If you take fast short shallow breaths your brain perceives it as an invitation to fight-flight-freeze; if you seep the air in and let it out slowly your brain will take it as an invitation to rest-and-digest, promoting parasympathetic activation. You’re going to be able to relax and feel so much better. |

Let’s start by trying a couple of exercises to get an understanding of what we mean when we refer to deepening the breath.

1. You can intentionally control your respiratory musculature by expanding the chest first then the belly on the inhale, and then gradually contract the abdomen (draw your navel backwards towards your spine) and deflate the chest on the exhale. Adding this type of directionality to your breathing patterns helps to slow down the breath and gain more control over the respiratory musculature (don’t lift your shoulders, unclench your jaw, relax your face…).

Using this deeper way of breathing we can move onto the second step.

2. Lengthening the exhalation (exhale + hold after exhale, don’t strain).

Have you heard the phrase, ‘waiting to exhale’? It’s often used when someone is experiencing uncertainty or stress. Every time you inhale you activate your sympathetic response a bit (and your heart speeds up a little, the vagus nerve is suppressed); if you hold the air in, that response is accentuated.

Conversely, every time you exhale you activate the parasympathetic response (the heart rate slows down a bit and the vagus nerve is activated); if you hold the air out for few seconds it will further facilitate the parasympathetic activation. To promote parasympathetic activation and vagus nerve stimulation you would need to gradually lengthen your exhale and pause after exhale (comfortably). This pause or gap usually happens quite naturally after some minutes of the deep breathing mentioned above.

TOOLKIT:

Using the deep-breathing technique above we’ll begin with simple breath ratios, for example Inhale for 6 seconds and then exhale for 6 seconds. Repeat for a few cycles. This is 1:1 breathing.

Next, and if accessible to you without strain, lengthen your exhalation to 8 seconds and introduce a short hold after exhale. So, 6-8-pause. You can gradually extend the ratio to inhale 6 seconds, exhale 8 seconds and hold for 4 seconds, 6-8-4. Repeat for a few cycles and gradually return to the comfortable breathing pace. (Again, don’t lift your shoulders, unclench your jaw, relax your face…).

Next, and if accessible to you without strain, lengthen your exhalation to 8 seconds and introduce a short hold after exhale. So, 6-8-pause. You can gradually extend the ratio to inhale 6 seconds, exhale 8 seconds and hold for 4 seconds, 6-8-4. Repeat for a few cycles and gradually return to the comfortable breathing pace. (Again, don’t lift your shoulders, unclench your jaw, relax your face…).

As you may notice when practicing these breathing techniques, moving attention away from the external to the internal creates better body awareness and better concentration. The same can be said for this next technique which utilises SOUND: (Good, good, good, good vibrations…)

This is a journey into sound (beat Dis)

| Research shows that chanting OM deactivates the limbic parts of the brain (some call it the lizard brain) involved in our behavioural and emotional responses, especially our fight-flight-freeze responses. Which, as previously mentioned, is where most people reside most of the time, due to busy and stressful lives. Next, we’ll learn how to use sound to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, our rest-and-digest response, and move away from the physiological effects of stress. |

The Yogis amongst you will be aware when chanting OM we experience a vibration sensation around the ears. Science suggests that this sensation is transmitted through the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. Since the vagus nerve branches out into the inner ear and larynx, controlling the opening and closing of the vocal cords and sound pitch, it appears to get stimulated during vocalisation of O and M sounds.

In addition, we always chant on the exhalation, which as we know from above, means that the vagus nerve is activated in its role as parasympathetic system manager. Also, chanting usually facilitates lengthening of the exhalation, which further amplifies the parasympathetic effect, as mentioned above. It’s a double-win!

In addition, we always chant on the exhalation, which as we know from above, means that the vagus nerve is activated in its role as parasympathetic system manager. Also, chanting usually facilitates lengthening of the exhalation, which further amplifies the parasympathetic effect, as mentioned above. It’s a double-win!

TOOLKIT:

If chanting isn’t already part of your practice and seems a little out there, don’t worry, I have a few options for you; firstly, you could chant OM, instructions below; or softly hum your favourite song, this is perfectly acceptable and may be the most accessible option for you; or practice Bhrāmarī prāṇāyāma (bee breath), instructions below. Give these three options a try and see which sits best with you. If you laugh along the way, that’s an added bonus.

- How to chant Om: (Om syllable by syllable—a-ā-u-ū-m-(ng)-(silence).)

With eyes closed take a deep inhale, as you exhale to sound the first two syllables, open the mouth wide (a-ā-). Pursing lips together helps stretch out the next two syllables (u-ū-). Place the tip of your tongue on the roof your mouth to sound the last two syllables (m-ng). Let the silence within you settle before inhaling again. Repeat for a minute or so, noticing the vibrations in your throat and skull. Keeping your eyes closed, return to your normal breathing. Notice if anything has changed. - To practice Bhrāmarī prāṇāyāma (Bee Breath) you lengthen the exhalation and make a long one-tone M sound, this is usually calming.

| Find a comfortable seated position, either on the floor or in a chair. Always balance effort and ease. Make a buzzing sound of moderate volume, but never force it. Keep your facial muscles loose, your lips lightly touching, and your jaw relaxed, with the upper and lower rows of teeth slightly separated. Prolong the buzzing sound on the exhalation as long as it’s comfortable and you can still inhale smoothly, without gasping for air. If you start to feel agitated, back off and return to normal breathing. |

Basic Bhrāmarī (without mudra or Ujjāyī breath.)

Sit comfortably and allow your eyes to close. Take a breath or two to settle in and notice the state of your mind. When you’re ready, inhale and then, for the entire length of your exhalation, make a low- to medium-pitched humming sound in the throat. Notice how the sound waves gently vibrate your tongue, teeth, and sinuses. Imagine the sound is vibrating your entire brain (it really is). Do this practice for six rounds of breath and then, keeping your eyes closed, return to your normal breathing. Notice if anything has changed.

What else can we do?

So, that’s a few simple ways you can work with the (fascinating) vagus nerve and feel a whole heap better. What else can we do? You’ve possibly been enjoying a permitted daily walk during lockdown. If this was new for you, don’t let it go as lockdown eases. If you can keep it in your schedule it will continue to do you good. The days are getting longer (here in the northern-hemisphere) and (generally) the weather is better, with restrictions lifting be sure to get outside, even if you can only manage a few minutes. Enjoy the fresh air, all that vitamin D and the gorgeous colours that nature’s showing-off just now. Did you know that being outside in the morning (best within an hour of waking), absorbing daylight through the eyes, sets chemicals in motion to help you sleep at night?

As studios, gyms and classes start up, get involved. If you’d rather practice at home and haven’t started already, there are now lots of resources online – a benefit of the recent past… Do what’s fun for you and you’re more likely to keep it up. Movement is proven to not only improve our physical but our mental health too. Make a daily date incorporating breathwork (prāṇāyāma), sound, and movement and you will be paving the way to wellness. (A sing-a-long dance party in the kitchen counts, even if you’re dancing by yourself!)

As studios, gyms and classes start up, get involved. If you’d rather practice at home and haven’t started already, there are now lots of resources online – a benefit of the recent past… Do what’s fun for you and you’re more likely to keep it up. Movement is proven to not only improve our physical but our mental health too. Make a daily date incorporating breathwork (prāṇāyāma), sound, and movement and you will be paving the way to wellness. (A sing-a-long dance party in the kitchen counts, even if you’re dancing by yourself!)

| And let’s not forget interaction, another key facet in human wellbeing, which we’ve all recently become acutely aware of. Whilst we might be implementing social distancing and masks for a while to come, your sparkly eyes and friendly wave go a long way to making another’s day special. And lord knows, we can all still interact online. Hit me up with questions, comments or just to say hi. Looking forward to being with you soon. |

Join the mailing list to be first to hear about what we’re doing, and when we’re doing it!

This blog post comes from: http://www.thebookoflife.org/how-to-lengthen-your-life/

CHAPTER 4: SELF: MOOD

How to Lengthen Your Life

The normal way we set about trying to extend our lives is by striving to add more years to them – usually by eating more couscous and broccoli, going to bed early and running in the rain. But this approach may turn out to be quixotic, not only because Death can’t reliably be warded off with kale, but at a deeper level, because the best way to lengthen a life is not by attempting to stick more years on to its tail.

One of the most basic facts about time is that, even though we insist on measuring it as if it were an objective unit, it doesn’t, in all conditions, feel as if it were moving at the same pace. Five minutes can feel like an hour; ten hours can feel like five minutes. A decade may pass like two years; two years may acquire the weight of half a century. And so on.

CHAPTER 4: SELF: MOOD

How to Lengthen Your Life

The normal way we set about trying to extend our lives is by striving to add more years to them – usually by eating more couscous and broccoli, going to bed early and running in the rain. But this approach may turn out to be quixotic, not only because Death can’t reliably be warded off with kale, but at a deeper level, because the best way to lengthen a life is not by attempting to stick more years on to its tail.

One of the most basic facts about time is that, even though we insist on measuring it as if it were an objective unit, it doesn’t, in all conditions, feel as if it were moving at the same pace. Five minutes can feel like an hour; ten hours can feel like five minutes. A decade may pass like two years; two years may acquire the weight of half a century. And so on.

In other words, our subjective experience of time bears precious little relation to the way we like to measure it on a clock. Time moves more or less slowly according to the vagaries of the human mind: it may fly or it may drag. It may evaporate into airy nothing or achieve enduring density.

If the goal is to have a longer life, whatever the dieticians may urge, it seems like the priority should not be to add raw increments of time but to ensure that whatever years remain feel appropriately substantial. The aim should be to densify time rather than to try to extract one or two more years from the fickle grip of Death.

Why then does time have such different speeds, moving at certain points bewilderingly fast, at others with intricate moderation? The clue is to be found childhood. The first ten years almost invariably feel longer than any other decade we have on earth. The teens are a little faster but still crawl. Yet by our 40s, time will have started to trot; and by our 60s, it will be unfolding at a bewildering gallop.

If the goal is to have a longer life, whatever the dieticians may urge, it seems like the priority should not be to add raw increments of time but to ensure that whatever years remain feel appropriately substantial. The aim should be to densify time rather than to try to extract one or two more years from the fickle grip of Death.

Why then does time have such different speeds, moving at certain points bewilderingly fast, at others with intricate moderation? The clue is to be found childhood. The first ten years almost invariably feel longer than any other decade we have on earth. The teens are a little faster but still crawl. Yet by our 40s, time will have started to trot; and by our 60s, it will be unfolding at a bewildering gallop.

The difference in pace is not mysterious: it has to do with novelty. The more our days are filled with new, unpredictable and challenging experiences, the longer they will feel. And, conversely, the more one day is exactly like another, the faster it will pass by in an evanescent blur. Childhood ends up feeling so long because it is the cauldron of novelty; because its most ordinary days are packed with extraordinary discoveries and sensations: these can be as apparently minor yet as significant as the first time we explore the zip on a cardigan or hold our nose under water, the first time we look at the sun through the cotton of a beach towel or dig our fingers into the putty holding a window in its frame. Dense as it is with stimuli, the first decade might as well be a thousand years long.

By middle age, things can be counted upon to have grown a lot more familiar. We may have flown around the world a few times. We no longer get excited by the idea of eating a pineapple, owning a car or flipping a lightswitch. We know about relationships, earning money and telling others what do. And as a result, time runs away from us without mercy.

One solution often suggested at this point is that we should put all our efforts into discovering fresh sources of novelty. We can’t just continue to live our small predictable and therefore ‘swift’ lives in a single narrow domain; we need to become explorers and adventurers. We must go to Machu Picchu or Angkor Wat, Astana or Montevideo, we need to find a way to swim with dolphins or order a thirteen course meal at a world-famous restaurant in downtown Lima. That will finally slow down the cruel gallop of time.

But this is to labour under an unfair, expensive and ultimately impractical notion of novelty. We may by middle age certainly have seen a great many things in our neighborhoods, but we are – fortunately for us – unlikely to have properly noticed most of them. We have probably taken a few cursory glances at the miracles of existence that lie to hand and assumed, quite unjustly, that we know all there is to know about them. We’ve imagined we understand the city we live in, the people we interact with and, more or less, the point of it all.

But of course we have barely scratched the surface. We have grown bored of a world we haven’t begun to study properly. And that, among other things, is why time is racing by.

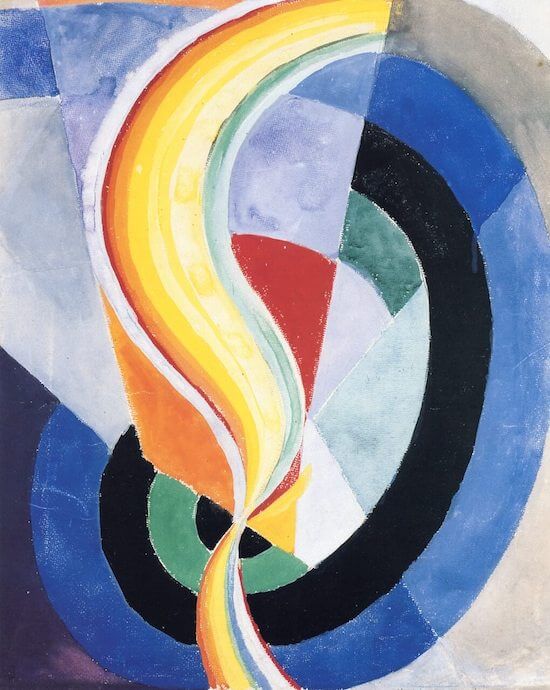

The pioneers at making life feel longer in the way that counts are not dieticians, but artists. At its best, art is a tool that reminds us of how little we have fathomed and noticed. It re-introduces us to ordinary things and reopens our eyes to a latent beauty and interest in precisely those areas we had ceased to bother with. It helps us to recover some of the manic sensitivity we had as newborns. Here is Cezanne, looking closely at apples, as if he had never seen one before and nudging us to do likewise:

One solution often suggested at this point is that we should put all our efforts into discovering fresh sources of novelty. We can’t just continue to live our small predictable and therefore ‘swift’ lives in a single narrow domain; we need to become explorers and adventurers. We must go to Machu Picchu or Angkor Wat, Astana or Montevideo, we need to find a way to swim with dolphins or order a thirteen course meal at a world-famous restaurant in downtown Lima. That will finally slow down the cruel gallop of time.

But this is to labour under an unfair, expensive and ultimately impractical notion of novelty. We may by middle age certainly have seen a great many things in our neighborhoods, but we are – fortunately for us – unlikely to have properly noticed most of them. We have probably taken a few cursory glances at the miracles of existence that lie to hand and assumed, quite unjustly, that we know all there is to know about them. We’ve imagined we understand the city we live in, the people we interact with and, more or less, the point of it all.

But of course we have barely scratched the surface. We have grown bored of a world we haven’t begun to study properly. And that, among other things, is why time is racing by.

The pioneers at making life feel longer in the way that counts are not dieticians, but artists. At its best, art is a tool that reminds us of how little we have fathomed and noticed. It re-introduces us to ordinary things and reopens our eyes to a latent beauty and interest in precisely those areas we had ceased to bother with. It helps us to recover some of the manic sensitivity we had as newborns. Here is Cezanne, looking closely at apples, as if he had never seen one before and nudging us to do likewise:

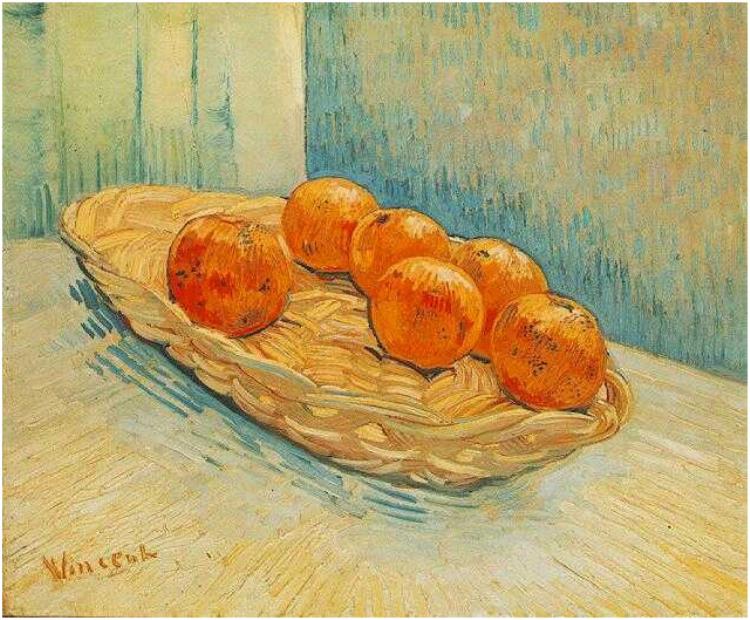

Here is Van Gogh, mesmerised by some oranges:

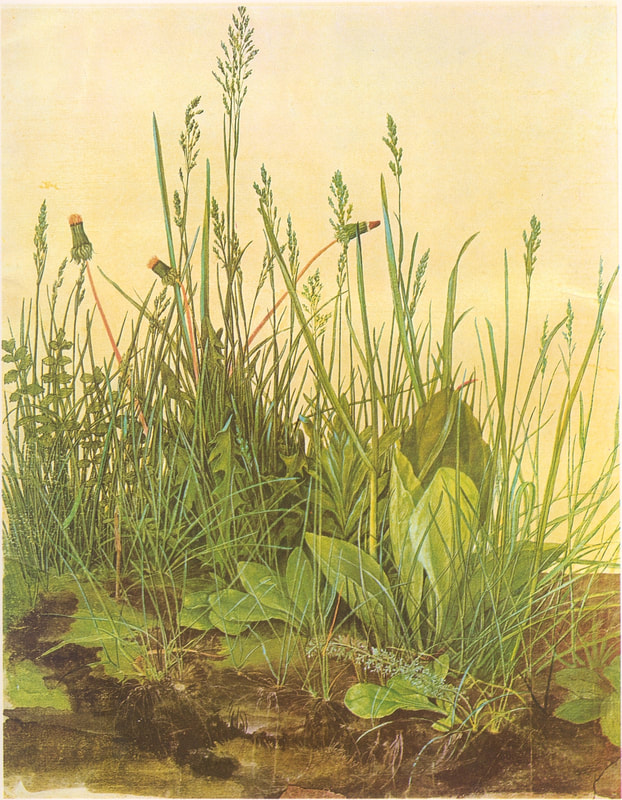

Here is Albrecht Durer, looking – as only children usually do – very closely at a clod of earth:

We don’t need to make art in order to learn the most valuable lesson of artists, which is about noticing properly, living with our eyes open – and thereby, along the way, savouring time. Without any intention to create something that could be put in a gallery, we could – as part of a goal of living more deliberately – take a walk in an unfamiliar part of town, ask an old friend about a side of their life we’d never dared to probe at, lie on our back in the garden and look up at the stars or hold our partner in a way we never tried before. It takes a rabid lack of imagination to think we have to go to Machu Picchu to find something new.

In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel The Idiot, a prisoner has suddenly been condemned to death and been told he has only a few minutes left to live. ‘What if I were not to die!,’ he exclaims. ‘What if life were given back to me – what infinity!… I’d turn a whole minute into an age…’ Faced with losing his life, the poor wretch recognises that every minute could be turned into aeons of time, with sufficient imagination and appreciation.

It is sensible enough to try to live longer lives. But we are working with a false notion of what long really means. We might live to be a thousand years old and still complain that it had all rushed by too fast. We should be aiming to lead lives that feel long because we have managed to imbue them with the right sort of open-hearted appreciation and unsnobbish receptivity, the kind that five-year-olds know naturally how to bring to bear. We need to pause and look at one another’s faces, study the evening sky, wonder at the eddies and colours of the river and dare to ask the kind of questions that open our souls. We don’t need to add years; we need to densify the time we have left by ensuring that every day is lived consciously – and we can do this via a manoeuvre as simple as it is momentous: by starting to notice all that we have as yet only seen.

In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel The Idiot, a prisoner has suddenly been condemned to death and been told he has only a few minutes left to live. ‘What if I were not to die!,’ he exclaims. ‘What if life were given back to me – what infinity!… I’d turn a whole minute into an age…’ Faced with losing his life, the poor wretch recognises that every minute could be turned into aeons of time, with sufficient imagination and appreciation.

It is sensible enough to try to live longer lives. But we are working with a false notion of what long really means. We might live to be a thousand years old and still complain that it had all rushed by too fast. We should be aiming to lead lives that feel long because we have managed to imbue them with the right sort of open-hearted appreciation and unsnobbish receptivity, the kind that five-year-olds know naturally how to bring to bear. We need to pause and look at one another’s faces, study the evening sky, wonder at the eddies and colours of the river and dare to ask the kind of questions that open our souls. We don’t need to add years; we need to densify the time we have left by ensuring that every day is lived consciously – and we can do this via a manoeuvre as simple as it is momentous: by starting to notice all that we have as yet only seen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed